The American Civil War was devastating to the young country, leaving over 620,000 men dead - more casualties than any previous American war (Kao). Not only did the remaining citizens have to recover from the massive blow to the population of young men, but they also had to find ways of coping with the returning soldiers, many of them amputees and unable to work, independently care for themselves, or provide for their families. Between 30,000 and 50,000 men survived the horrors of the war, but left their limbs on the battlefields (Kao). How did society adapt to this new class of citizens? These men were both a physical reminder of the devastation of the Civil War and a representation of the advancement of medicine; the photographer of amputees chose to emphasize the latter over the former. In the photo album I constructed, I organized the photographs chronologically; that is, in the order of the life of an amputee. First, the exhibit of the femur, shattered irreparably. Next, two images of the amputation taking place, followed by images of the resulting amputee. Last, the amputee in society and his life after the war. The images of the amputations are sterile, organized and calm - blatantly staged, but confirming the photographer’s desire to idealize a modern medical practice. Photographs of Civil War amputees all follow a tradition of exposing as much of the scarring as possible. To the 21st century eye a graphic portrayal of amputation is brutal and disturbing; however, in the 19th century, these images were instead a manifestation of the advancement of modern medicine in that the subjects had survived an injury previously though to be fatal. The photographer’s role in documenting Civil War amputees was to provide an idealized account of their social condition by using his photographs not to expose the apparent effects of war, but instead to showcase the advancements of medicine.

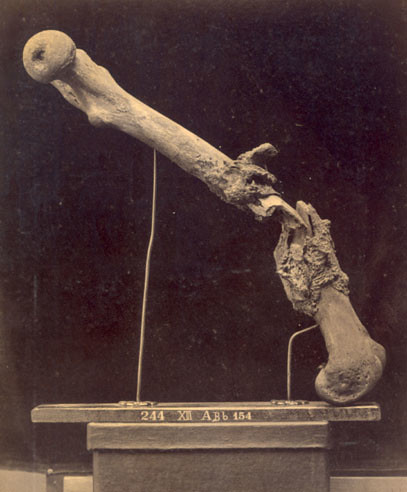

I chose the first image in the album, Necrosis and Exfoliation and Deposits of Spongy Callus after a Gunshot Fracture of the Left Femur, as an introduction to understanding the devastating wounds caused by Civil War era ammunition.

It is difficult to comprehend the reasons amputation was such a widely used practice; this humbling image of the largest bone in the human body, annihilated beyond the repair of even modern medicine, allows for the 21st century viewer to better understand the death tolls Civil War surgeons were forced to confront. During the war, soldiers used a cone-shaped lead bullet called the “Minie ball;” heavy and soft, it tended to flatten and expand upon hitting bone, causing “large, gaping holes, splintered bones, and destroyed muscles, arteries and tissues beyond any possible repair” (Goellnitz). Surgeons considered soldiers with head or cavity injuries hopeless. Of the wounds recorded in the Civil War, over seventy percent were to the extremities and, at under fifteen minutes per operation, amputation was the quickest, easiest, and therefore most common treatment of an injured soldier (Anonymous, “Civil”). Conditions for surgery were crowded, loud, dirty and unsterilized; if a patient survived the initial shock and blood loss, he was likely to develop infection such as pyemia or tetanus, each having a mortality rate of around 90% (Goellnitz). The purpose in including these statistics and this background is to establish that these men were not expected to survive. Amputee victims were, of course, a harsh reminder of the devastation of the Civil War, but were also living exhibits of society’s advancements in medicine. The photograph of the obliterated femur is a cold reminder of the mortality of the Civil War solider.

It is difficult to comprehend the reasons amputation was such a widely used practice; this humbling image of the largest bone in the human body, annihilated beyond the repair of even modern medicine, allows for the 21st century viewer to better understand the death tolls Civil War surgeons were forced to confront. During the war, soldiers used a cone-shaped lead bullet called the “Minie ball;” heavy and soft, it tended to flatten and expand upon hitting bone, causing “large, gaping holes, splintered bones, and destroyed muscles, arteries and tissues beyond any possible repair” (Goellnitz). Surgeons considered soldiers with head or cavity injuries hopeless. Of the wounds recorded in the Civil War, over seventy percent were to the extremities and, at under fifteen minutes per operation, amputation was the quickest, easiest, and therefore most common treatment of an injured soldier (Anonymous, “Civil”). Conditions for surgery were crowded, loud, dirty and unsterilized; if a patient survived the initial shock and blood loss, he was likely to develop infection such as pyemia or tetanus, each having a mortality rate of around 90% (Goellnitz). The purpose in including these statistics and this background is to establish that these men were not expected to survive. Amputee victims were, of course, a harsh reminder of the devastation of the Civil War, but were also living exhibits of society’s advancements in medicine. The photograph of the obliterated femur is a cold reminder of the mortality of the Civil War solider.The first instincts of the 21st century viewer, upon seeing the graphic images of an amputee is to grimace in disgust, gasp with horror, or sigh with pity.

The photographers of Alfred Stratton, pensioned at twenty-five dollars a month and provided with artificial arms and Eben E. Smith wanted to produce a different reaction from their 19th century contemporaries. These men were living, breathing evidence of a successful operation, thus reflecting on the advancement of medicine as a whole. After the Civil War, the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office collected photographs of particular medical cases and published them as Photographs of Surgical Cases and Specimens Taken at the Army Medical Museum (Anonymous, “Magical”). Specimens: these photographs did not capture the horror of a war veteran in a portrait; rather they were likenesses with the intention of illustrating the advancement of the surgeon’s technique and the miracle of the specimen’s survival. The mortality rate of an upper arm amputation, like Alfred Stratton’s, was about 24%, while a hip amputation, like Eben E. Smith’s, was 83% (Goellnitz). These men, especially Smith, were not supposed to live. But they did.

The way in which these men were documented truly shows the photographer’s purpose as showcasing the progression of science. First, the men are positioned so that as much of their scarring is visible. Now, this is used in modern photography as a shock factor, to force the viewer to confront the wounded subject. But, Smith’s likeness even has a mirror positioned behind him to reveal another possible angle of his limb, suggesting not a forced confrontation, but instead a medical curiosity. The mirror encourages the viewer to peer deeper into the photograph to search for the details, rather than being blatantly accosted by them. The presence of the mirror solidifies the idea that this image is not a portrait of a distraught man without a limb, but instead a likeness of his medical miracle. Second, the men are both fully dressed with the exception of their injured limbs - if this were a sensational appeal to the horrors of war, the men could have easily worn clothes that were pinned to show the loss of their limbs. Instead, Alfred Stratton sits with pants and no shirt to show the scars on his arms in order that they might be observed as evidence of medical advancement - the scars serve as proof that he was wounded badly, underwent the surgery and lived. Eben E. Smith is wearing a buttoned-up shirt and a tie, while not wearing pants. He is modestly covered, but not artistically - a simple, awkward cloth protects his privacy. Again, the effect of a missing leg could have been captured while he was wearing pants, but the photographer chose to clothe his upper half and not his lower half to shift the focus to the details of the surgical technique used to sew together his limb. The photographers of amputees meant to document and exhibit these men as trophies, physical proof of the successful advancement of medicine.

The way in which these men were documented truly shows the photographer’s purpose as showcasing the progression of science. First, the men are positioned so that as much of their scarring is visible. Now, this is used in modern photography as a shock factor, to force the viewer to confront the wounded subject. But, Smith’s likeness even has a mirror positioned behind him to reveal another possible angle of his limb, suggesting not a forced confrontation, but instead a medical curiosity. The mirror encourages the viewer to peer deeper into the photograph to search for the details, rather than being blatantly accosted by them. The presence of the mirror solidifies the idea that this image is not a portrait of a distraught man without a limb, but instead a likeness of his medical miracle. Second, the men are both fully dressed with the exception of their injured limbs - if this were a sensational appeal to the horrors of war, the men could have easily worn clothes that were pinned to show the loss of their limbs. Instead, Alfred Stratton sits with pants and no shirt to show the scars on his arms in order that they might be observed as evidence of medical advancement - the scars serve as proof that he was wounded badly, underwent the surgery and lived. Eben E. Smith is wearing a buttoned-up shirt and a tie, while not wearing pants. He is modestly covered, but not artistically - a simple, awkward cloth protects his privacy. Again, the effect of a missing leg could have been captured while he was wearing pants, but the photographer chose to clothe his upper half and not his lower half to shift the focus to the details of the surgical technique used to sew together his limb. The photographers of amputees meant to document and exhibit these men as trophies, physical proof of the successful advancement of medicine.Next in the album, there are two images of the scene of an amputation surgery: Battlefield Surgery 101 and Camp Letterman After the Battle of Gettysburg, PA.

The photographers of both of these images staged the scenes in an attempt to show modern surgical practices of the Civil War as organized, humane and sterile. But where are the other men, dying on the crowded floor, bleeding and screaming for relief from their pain? There is not a speck of blood anywhere in these images. The men in Battlefield Surgery are in military uniforms - and one is even wearing a hat- while the surgeon in Camp Letterman is wearing a vest and a clean white shirt! The wreath and garland lavishly decorating the tent in Camp Letterman is laughably absurd. There is no panic, fear or adrenaline in these stagnant images. In Battlefield Surgery, the straight horizontal lines of the roof, the top of the carriage and the table compliment the straight vertical lines of the two standing men, the table legs, the front and back of the carriage and the pillars of the structure - there are no diagonals crossing the image to add any element of chaos. This post and lintel type of construction of the scene provides an unnatural, forced sense of stability and firmness to the piece. Similarly, Camp Letterman features a lot of men standing with their feet together and their hands on their hips, quietly staring at the patient - a true battlefield hospital of course would not be this overstaffed and peaceful.

The photographers of both of these images staged the scenes in an attempt to show modern surgical practices of the Civil War as organized, humane and sterile. But where are the other men, dying on the crowded floor, bleeding and screaming for relief from their pain? There is not a speck of blood anywhere in these images. The men in Battlefield Surgery are in military uniforms - and one is even wearing a hat- while the surgeon in Camp Letterman is wearing a vest and a clean white shirt! The wreath and garland lavishly decorating the tent in Camp Letterman is laughably absurd. There is no panic, fear or adrenaline in these stagnant images. In Battlefield Surgery, the straight horizontal lines of the roof, the top of the carriage and the table compliment the straight vertical lines of the two standing men, the table legs, the front and back of the carriage and the pillars of the structure - there are no diagonals crossing the image to add any element of chaos. This post and lintel type of construction of the scene provides an unnatural, forced sense of stability and firmness to the piece. Similarly, Camp Letterman features a lot of men standing with their feet together and their hands on their hips, quietly staring at the patient - a true battlefield hospital of course would not be this overstaffed and peaceful.  The abnormality of these scenes really establishes the presence of the photographers, and their desire to create an image promoting the idealization of the medical practice of amputation.

The abnormality of these scenes really establishes the presence of the photographers, and their desire to create an image promoting the idealization of the medical practice of amputation.The last photograph in the album, Washington, D.C. Maimed soldiers and others before office of U.S. Christian Commission shows the photographer’s attempt at normalizing the new class of amputees with which post-war American society was forced to cope.

The Christian Commission, provided “goods and supplies” to soldiers during the Civil War, and also after the war was over (Anonymous, “USCC”). True, the amputees in this image are outside of a charity organization, presumably having no where else to go to provide for themselves or their families. However, the amputees do not stand out immediately among the crowd as having a sense of otherness from their peers. They are on the same level plane as the rest of the subjects of the photograph, and truly have the same posed posture and direct gaze as those around them. It even takes a bit of concentration to notice the man without an arm behind the man on crutches. There are women in the photograph with nice dresses along with men in tall top hats, presumably people who did not need to beg for help from the Christian Commission; this illustrates that the photographer did not want these meant o be viewed as equals to beggars, but instead to a higher class of people. These men blend into the crowd of civilians as their equals. Once again, the practice of amputation is idealized through photography; the photographer, through this image, attempts to show that the amputees are reintegrated back into a welcoming society.

The Christian Commission, provided “goods and supplies” to soldiers during the Civil War, and also after the war was over (Anonymous, “USCC”). True, the amputees in this image are outside of a charity organization, presumably having no where else to go to provide for themselves or their families. However, the amputees do not stand out immediately among the crowd as having a sense of otherness from their peers. They are on the same level plane as the rest of the subjects of the photograph, and truly have the same posed posture and direct gaze as those around them. It even takes a bit of concentration to notice the man without an arm behind the man on crutches. There are women in the photograph with nice dresses along with men in tall top hats, presumably people who did not need to beg for help from the Christian Commission; this illustrates that the photographer did not want these meant o be viewed as equals to beggars, but instead to a higher class of people. These men blend into the crowd of civilians as their equals. Once again, the practice of amputation is idealized through photography; the photographer, through this image, attempts to show that the amputees are reintegrated back into a welcoming society.It would be very simple for the 21st century viewer to dismiss these images as being grotesque reminders of the cruelty of war. However, I argue that to the 19th century eye, these images of amputees were symbolic of the advancement of medicine. The morality rate for these men was so high, that it was spectacular that they survived, even if it mean a lifetime without limbs. Documenting these men was documenting a modern miracle, not a horrid representation of war. The mutilated femur, the graphically posed amputees, the painfully theatrical depictions of the surgery, and the intentional blending in of the amputees after their reintroduction into society: all of these images represent the photographer’s idealization of the practice of amputation. This operation was idealized by photographers because it allowed for these soldiers to live. And in a war where there were more casualties than any other previous war America had ever seen, an operation that could save lives was a miracle.

Works Cited

Anonymous. “Civil War Amputations.” North Carolina Museum of History. NC Department of Cultural History. Web. 18 November 2010.

Anonymous. “Magical Stones and Imperial Bones: Rare Books, Manuscripts and Photographs from the Collections of the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine.” Countway Library of Medicine. Countway Library of Medicine at Harvard. Web. 20 November 2010.

Anonymous. “USCC History.” USCC. US Christian Commission: Heroes of Faith During the Civil War. Web. 18 November 2010.

Goellnitz, Jenny. “Civil War Battlefield Surgery.” Ehistory at Ohio State University. Ehistory. Web. 18 November 2010.

Kao, Audiey. “Role of Physicians in Wartime.” Virtual Mentor. 2.5 (2000). Web. 18 November 2010.